When high variance strategies win

Over the holidays I find myself playing lots of board and card games. This year I ended up playing several games of Wizard. It's a trick-taking game where you bid on the number of tricks you'll take in the next game.

What makes this of interest1 to me as a statistician is the results of our games. While I thought I had played rather well, I never won2 any of about a half-dozen games. I had however came in second every game and when aggregating scores across games I won by a landslide 3. So how does that happen?

Roughly speaking, there's two strategies players can follow.

- Tortoise/Low Variance

- This strategy is to bid low and slough off cards to ensure you don't take too many tricks. This strategy is reliable and it's very hard to not make your bid. However, you don't get quite as many points this way.

- Hare/High Variance

- This strategy is to bid high and do your best to take as many tricks as possible. This strategy is difficult and relies heavily on luck. However, you are rewarded well when you do make your bid.

I typically followed the first strategy, everyone else followed the second. So why didn't slow and steady win the race?

To see what's happening let's consider a simple game: we draw random numbers from a distribution and the highest number wins. We'll let the players choose the variance of a Normal distribution 4. Let's start with just two players

Let \(X \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0, \sigma)\) and \(Y \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0, 1)\). We can calculate the probility that \(X\) will win as follows:

\begin{align*} \Pr(X > Y) &= \Pr(0 > Y - X) \\ &= \Phi(0) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \end{align*}From this it's obvious that a high-variance strategy is not beneficial; regardless of the variance, the game is just a coin flip. However, things start getting more complicated when we start introducing more players.

Let \(X \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0, \sigma)\) and \(Y_{i} \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0, 1)\) for \(i = 1, 2, \dots, n\). Now we again calculate the probability that \(X\) wins:

\begin{align*} \Pr(\cap_{i=1}^{n} X > Y_{i}) &= \Pr(X > \max{Y_{i}}) \\ &= E[\Phi(X)^{n}] \end{align*}To evaluate this expectation we'll have to resort to numerical methods. The first that comes to mind is a Monte Carlo integration.

monte_carlo <- function(variance, nOpp, nSims) { draws <- rnorm(nSims, 0, sqrt(variance)) vals <- pnorm(draws, 0, 1)^nOpp return(mean(vals)) } set.seed(42) monte_carlo(2, 4, 100000)

0.257292028255972

So with 4 opponents, a higher variance strategy wins almost 25% of the time; about 1.25 times as much as would be expected.

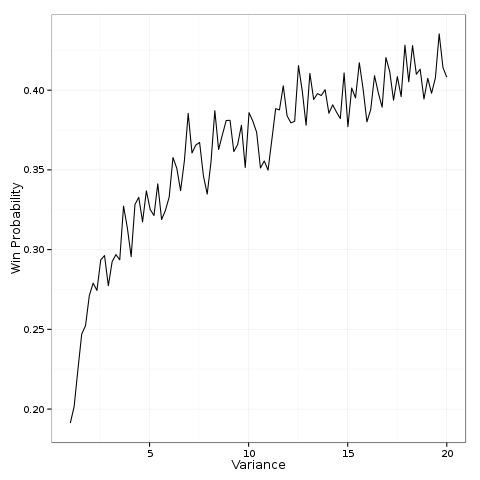

Now, let's plot the win probability as a function of the variance.

library(ggplot2) var <- seq(1, 20, length.out = 100) winprob <- sapply(var, function(x) monte_carlo(x, 4, 1000)) df <- data.frame(var = var, winprob = winprob) fig <- ggplot(df, aes(x = var, y = winprob)) + geom_line() + xlab("Variance") + ylab("Win Probability") + theme_bw() print(fig)

From this figure we see that pursuing a high-variance strategy dramatically increases the probability of success. As you increase the variance it increases from baseline (20%) and asymptotically approaches the ceiling (50%).

This explains why I was always losing. In games where the winner is determined by the maximum score, a higher variance strategy is favored. But then why did I "win" when we aggregated our scores?

The answer has to do with the mean. The Hare strategy has a high variance, but a slightly lower mean. Averaging games reduces the variance while keeping the mean the same. Over the long run, the higher mean of the Tortoise will inevitably lead to victory with high probability.

Footnotes:

Beyond the usual hidden knowledge and inference problems of card games in general.

Not that I'm hyper-competitive and compulsively keeping track of my wins

And no, I wasn't just desperately finding some way to eke out a win; see above footnote.

We can justify this through an appeal to the Central Limit Theorem in the case of games which consist of independent repeated trials (like Wizard).